Communication

Downloaded content date

Communication

A high level of communication skills is the single most important tool a professional can have when dealing with people with a palliative illness and at the end of life. Conversations about death and dying or a request for assistance to die can be challenging, emotional and complex.

These conversations require sensitivity, professionalism and a clear understanding of the legal and ethical frameworks. Without the appropriate knowledge and skills to manage these challenging conversations, there will be a significant impact on the nursing workforce's role and practice, as well as on patients.

Communicating at this level requires a high degree of emotional intelligence and self-reflection. Professionals engaging in these difficult discussions must demonstrate empathy and compassion while maintaining objectivity. The personal beliefs around end-of-life care or dying from those we care for may be influenced by unresolved suffering, loneliness or a sense of hopelessness and hard to set aside.

It is important to acknowledge this distress and not dismiss it; it is not illegal to discuss a patient’s fears or concerns about dying. Open and honest communication is essential in providing person-centred, holistic care. However, encouraging, facilitating, or promoting assisted dying is illegal. Ensure that any discussion stays within the bounds of ethical and legal practice.

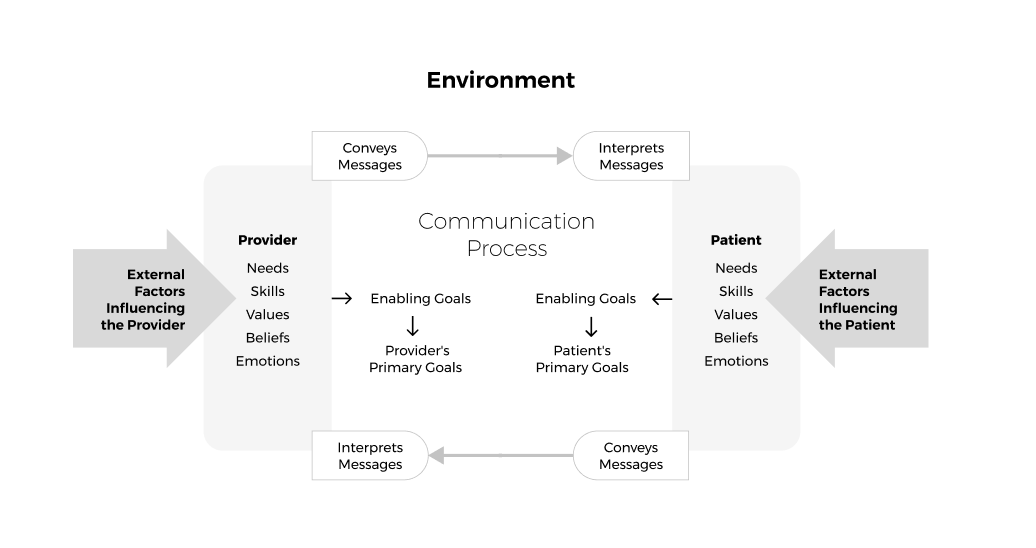

The complexity of these communications is demonstrated in the following model:

Illustration based on diagram by Feldman - Stewart et al (2005)

Two people can be in the same room, sharing the same moment but be in completely different ‘worlds’, influenced by a range of different factors.

Communication skills

The key skills to support communication are:

- active listening, including checking understanding and reflecting

- use of open questions

- body language, posture, eye contact

- responding in a genuine and non-judgemental way, with, honesty, empathy, and avoiding jargon.

The World of Work (2019) developed a framework of principles to guide effective communication called ‘The 7 C's of Communication - The World of Work Project.'

Its principles state that communication should be:

- Clear.

- Correct.

- Concise.

- Complete.

- Concrete.

- Considered.

- Courteous.

Self‑awareness helps professionals communicate well, understand how others see them, and support their own wellbeing at work.(Sutton et al. 2015). Focusing on the person and giving them complete attention allows professionals not only to hear what is being said but also to read body language and nonverbal cues. In other words, does it match that verbal communication? Are there cues that could lead to deeper exploration rather than just taking words at face value?

Mehrabian’s 7-38-55% rule (1967) tells us that most communication is non-verbal:

- 7% words

- 38% tone of voice

- 55% body language

Therefore, just listening is not enough to determine all the nuances of a conversation. In addition, how we appear to others and our awareness of this are just as important; they can either improve the experience of a difficult conversation or make it more challenging.

The use of body language, including touch, can demonstrate kindness and compassion, influencing how professionals are perceived. Chochinov (2023) calls this the ‘care tenor’ or ‘tone of care’, which deeply influences a patient’s sense of dignity.

Challenges in communication

There are many challenges with communication, and we don’t always get it right. Recognising these challenges is key to developing management strategies that help minimise their impact. Some common challenges may include the following:

- time

- lack of knowledge and skills

- environment- geography, noise, intrusive, lack of privacy

- expectations

- conflict

- distress

- fear

- lack of confidence

- family dynamics

- methods of communication—face-to-face or remote

- cognitive impairment—dementia, learning disability

- sensory impairment—deafness, poor sight.

We often have an awareness of impending conversations and difficulties before they happen. Taking the time to assess the potential challenges before undertaking conversations can lead to improved outcomes.

However, unexpected topics may arise during conversations, such as assisted dying, so it is helpful to have a plan for how you will manage them if they do. This can prevent you from feeling pressured, upset, or concerned. Remember to be honest - if you are unable to answer a question, say so.

In Dr. Katherine Mannix’s book (2021) ‘Listen: How to Find the Words for Tender Conversations’, she discusses creating space and having tender conversations that are supportive for patients and carers when facing the momentous emotional challenges that living and dying from an illness can bring.

A helpful way to manage and cope as a nurse at the end of your shift is to use the ‘Going home checklist’, developed by the charity MIND.

Assisted dying

Regardless of the context of care or area of practice, all health professionals must keep communication channels open so that the patients in their care can express any concerns, needs, or expectations. This may also include a patient's desire to engage in conversations about dying or assisted suicide.

The key to responding is to ensure we maintain the principles of effective communication. These principles aim to support nurses and health care support workers in undertaking and navigating the difficult conversations surrounding end-of-life and assisted dying, while maintaining compassionate patient care and adhering to legal and professional boundaries.

The overriding principle is one of support – support for both the person seeking information and for the nurse being asked. You must avoid giving any information or suggested actions or advice that could be interpreted as encouraging assisted dying.

When faced with these challenges, the following may be helpful when having conversations:

- Listen and acknowledge: Patients making such statements may be experiencing distress, fear or a sense of loss of control. Active listening and acknowledgement can help validate feelings without endorsing any requests. This includes open-ended questions to explore any further thoughts.

- Clarify the patient’s request: It is essential to understand why requests have been made or clarify the meaning of any request that requires a shared understanding. Reassurance, symptom relief, or emotional support may be sought; ask gentle follow-up questions to gain a deeper understanding of any concerns.

- Provide clear information: The legal position on assisted dying should be explained in collaboration with the medical team while informing patients about available palliative care and pain management options. Avoid giving advice or suggesting actions that could be interpreted as assisted suicide. When giving information, ensure it meets individual needs, considering health literacy, neurodiversity, preferred language, and whether it needs to be in an accessible format.

- Explore underlying concerns: Many patients requesting assistance to die may be experiencing complex symptoms, psychological distress or social isolation. Conduct a holistic assessment of physical, emotional, spiritual and social needs. Addressing these concerns is essential and may require referrals and involvement of the appropriate health and social care professionals.

- Involve the multidisciplinary team: Working with palliative care and other specialists can provide patients with holistic support. Consider involving other team members if additional emotional or practical support is needed. You may also seek support from more experienced colleagues.

- Document discussions appropriately: Record key points of conversations in the patient’s records in line with the NMC Code (2018) on record-keeping for registrants and for non-registrants, adhere to local policy and Codes, ensuring that concerns and interventions are clearly noted. Documentation should include the patient's words, your responses, and any referrals or actions taken.

Having these conversations can be challenging and knowing where to start and what to say can be difficult. Below is a bank of phrases that you may find helpful when having these conversations. This is not an exhaustive list and should be used as an additional resource when having these conversations:

|

Responding to patients and family members |

|

“May I ask why you are asking me about assisted dying?” |

|

“Can you help me understand what you know about assisted dying?” |

|

“I’m sorry I can’t share my personal view, but I can explain about the current situation in …. ” |

|

“You may have heard about ‘assisted dying’ being discussed on the news, but it is important to know there is different legislation in the different countries across the UK and it is currently illegal across the UK….” |

|

“May I ask if you have discussed this with your family?” |

|

“May I ask if you have discussed this with anyone else?” |

|

“May I ask if this was your decision alone, or was it suggested to you?” |

|

“This must be a very difficult decision for you… it is important we help you understand the process…” |

|

“I can share what I know about assistant dying, but I will ask someone who has more knowledge than me about the current situation to speak with you, if that is ok?” |

|

“I am sorry, I don’t know the answer to that … but let me find out … or I could ask… to speak with you…” |

|

“Let me suggest you speak with your GP/consultant before making a final decision.” |

Further information

- RCN position on assisted dying in the UK and Crown Dependencies | Royal College of Nursing

- Assisted dying | Royal College of Nursing

- British Medical Association. Responding to patient requests for assisted dying

- Hospice UK. Assisted Dying Position Statement

- Marie Curie. Assisted Dying in the UK Resource

- Bustin et al. 2024. A meta synthesis exploring nurses experiences of assisted dying and participation decision-making

- Refolo et al. 2025. Attitudes of physicians, nurses and the public toward end-of-life decision in European countries: an umbrella review

- Wareing 2025. Implications of assisted dying for nursing practice.

Resource lead(s)

The resource lead(s) is responsible for